I’m always trying to do something new with millets and bring them into everyday dining because they are healthy, seasonal and affordable. In South India, they were actually the ancient traditional staple, not rice or wheat as it is today, and so they can be said to be perfect for Macrobiotic diets here. Different varieties of local millets have featured on this blog in recipes past (I’ve linked to a few at the end of this post). Today, the star is ragi, which you may also know as finger millet, teff or kezhvaragu.

Ragi is rich in calcium, iron and antioxidants, as well as high in fibre. This means that its benefits include everything from weight control to skin rejuvenation to curing anaemia. A dry-season crop that tolerates many different kinds of soil, it is easy to cultivate. It features in a large variety of South Indian dishes, from Kerala puttu to Karnataka ragi mudde to the koozh that is offered to the Goddess in Tamil Nadu. It is also eaten everywhere from Vietnam to numerous countries in Africa, where it originated.

I want to share with you the recipe for ragi millet dosa. Dosa is a South Indian crepe, similar to chilla. It is popularly made with rice flour, which I substitute almost entirely with ragi millet. It’s always exciting to add your own twist to something traditional. That’s the challenge of cooking as well – you can’t just throw in something and hope it sticks. How do you combine flavours so they work well and complement one another? It may seem simple and obvious to take two South Indian staples – ragi millets and dosas – and put them together. But this is not so, because in the case of any millet dosa, it is not only a matter of ingredients. The main question is: will the crepe peel off beautifully? Ragi has a sticky consistency, which can make this tricky. As those of us who make dosas regularly know, certain ingredients are added or removed to facilitate this peeling. This is why I still use a little bit of rice flour in the batter. Rice flour both adds crispiness to the dosa, as well as enables it to peel off properly.

As I’ve mentioned in the past, I ensure that all my powders and flours are homemade, ground by a trusted small mill. We grow both rice and ragi on our farm, so I know for sure that the ingredients in this dish, and any rice-based dishes eaten at home, are organic.

To come back to dosas and twists on the same – you can make your own variations of the dish below by adding vegetables to the crepe after it has been folded, or serving it with an assortment of chutneys. Here, I give you the recipe for a simple peanut chutney, which is a current favourite (peanuts are also grown on my farm). Ragi millet dosa is something I reach for often when I try to stay fit, and it’s always a satisfying meal.

Living in South India, dosa (or dosai) is something I’ve taken for granted. It really is a universally loved dish, as this story about my dog Coco will tell you. When she was pregnant years ago, she absolutely craved dosas! I would have one made especially for her every day, and she would simply refuse to eat it if it did not contain salt! My Coco is now sixteen years old and going strong, and the healthiest in my house since she eats fresh food every day. Now, her son Max also craves dosas, probably influenced by his mother’s taste during her pregnancy with him, and I always share mine with them both.

Ragi Millet Dosa

(Yield: 6 dosas)

Ingredients

½ cup ragi flour

1 tablespoon rice flour

1 teaspoon cumin

1 teaspoon paste of green chilli and ginger

1 tablespoon grated coconut

¾ cup water

1 tablespoon yoghurt

Finely chopped curry leaves

Finely chopped onions

Salt to taste

In a bowl, mix the ragi and rice flours in water until there are no lumps. Then add all the remaining ingredients. Stir until they all blend well together and become a smooth batter. Do not add too much water as this will make the batter too thin.

These dosas can either be prepared immediately, or the batter can be left to sit for about half an hour, letting the flavours blend more.

To fry a dosa is like frying any crepe. Add a few drops of oil on a heated iron griddle. Now lower the flame and pour 1 small cup of the batter onto the griddle, and spread it out in a circular motion until it is spread thin. Dot the edges with oil and increase the flame to high. Allow the dosa to turn dark on the edges, then flip over and allow to fry for a few minutes. Flip again once before you take it off the stove. Fold and serve with the peanut chutney, or a condiment of your choice.

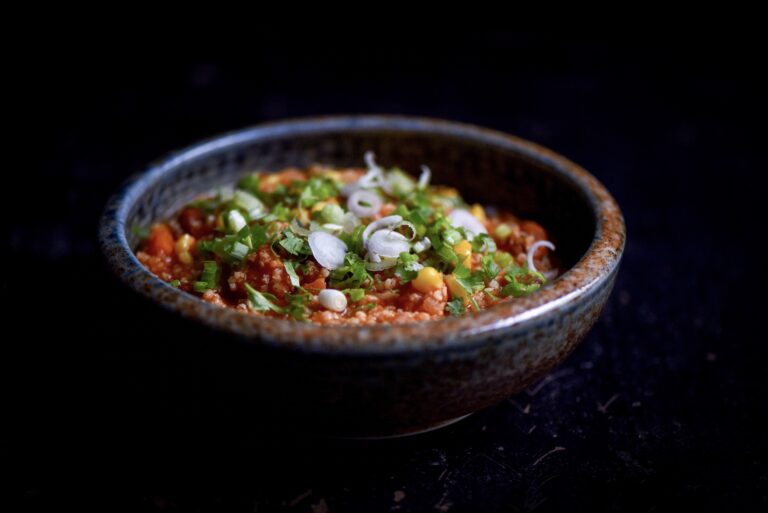

Peanut Chutney

(Yield: 1 cup)

Ingredients

½ cup roasted peanuts

1 teaspoon channa dal

1 teaspoon udad dal

1½ teaspoons tamarind paste

1 teaspoon grated ginger

¼ cup water

2 red chilies

A sprig of curry leaves

A few drops of oil

Salt to taste

Sauté the dals in a few drops of oil. Once they turn golden, add the dals along with the peanuts and ginger in a blender. Blend until coarse.

Now, to temper the chutney. Put a few drops of oil in a pan and add the mustard seeds and cumin seeds. Wait till they splutter and then add the red chillies and curry leaves. When they have been coated in the hot oil, immediately pour the tempering over the chutney. It is now ready to be eaten as a dip with the crispy hot dosas.

I’m an evangelist when it comes to millets and truly believe in their ability to transform our unhealthy modern diets. This is why they have featured so many times on this blog. If you’re curious about more dishes that incorporate these simple and satisfying ingredients, do check out this tag and spend some time exploring my past recipes. Here are a few of my favourite selections from the same: little millet rice with beans poriyal, chakkara pongal and vegan chili.