My children are all grown up and all of them live away from me, so every time they come to visit, I always try to think of what they will enjoy eating during their stay. One of my sons loves chocolate cake, so this particular treat is the welcome home dish that I currently have in the oven, ahead of his next arrival. It looks so beautiful that I couldn’t resist picking up the camera – and subsequently came the idea of sharing the recipe with you too.

Before I began to bake, many years ago now, we would often order from a friend of ours who used to bake from her home in Chennai too. Hers was one of the most fantastic chocolate cakes we had ever tasted, and it remains the benchmark for us all. It served as my inspiration too, when I became a baker myself.

Creating this recipe of my own was the result of many trials, exploring recipes from across cookbooks and the Internet, tweaking them based on my taste and my experience. Eventually, I formed a chocolate cake recipe that hit the spot, and became a personal benchmark. While my almond cakes are the most popular among customers (hyperlink), it’s this chocolate cake that is my own family’s favourite.

When I think about the experiments that lead toward this recipe, and indeed many others, I feel grateful for my blogger and Instagram friends and the accounts I have followed over the years who inspired me – both in terms of food and in terms of photography.

But there are many things that I have been contemplating lately about the world of food blogging and how it is changing. Now that re:store’s own online presence is over seven years old, I am able to observe and comment on the vast shifts that have taken place in this time and I wonder about what is still to come. For instance – many of the people whose work I used to look forward to no longer post, or sometimes have even disappeared altogether. Even though new bloggers have come up, some equally fantastic, there was a sense of community in the past that is less experienced today. It all feels different now, both as a creator and as someone who enjoys the content. I wonder if you feel similarly, or if you have other thoughts?

Then, there is the dominance of reels. Food photography as a genre is dwindling, and to be honest I don’t see the kind of aesthetic that I used to love exploring online and which challenged me to keep growing as a photographer too. While I respect reels as their own format, they are not for me. Even as photography loses popularity, I pick up my camera time and again because it is an artform that I am passionate about, and because in certain ways I would define myself as being old school – especially in the sense that I believe that if the going is good, keep going.

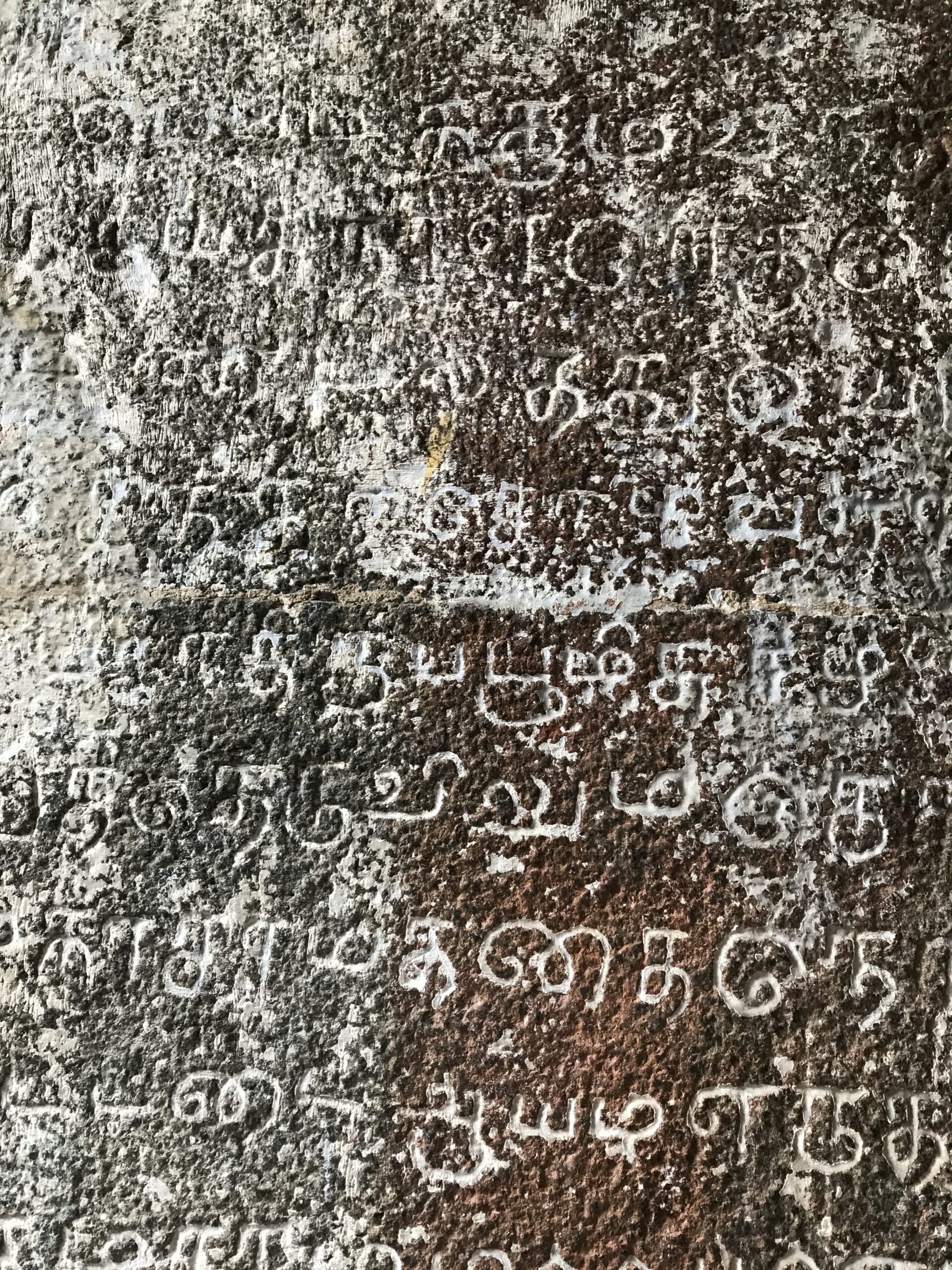

The going is good, so to speak, when it comes to photography. I am just as enthused and as inspired as ever as a photographer, and some of you may know that my explorations in this medium go beyond shooting for this blog. I also work with still life and nature themes, and I’ve been fortunate to have received gallery support for the same, and I sometimes accept commercial commissions too.

I still approach every kind of shoot with my old and faithful Nikon and the lenses I’ve used all these years, and remain perfectly happy with the outcomes. I don’t intend to go in for an upgrade because I know I don’t need to. Although I love finding new appliances for the kitchen, somehow with photography the tried and tested just works for me. I like to think that my not constantly seeking out new technology helps reduce my personal impact on landfills. None of us is perfect and none of us is going to avoid creating waste, but being mindful about our consumer choices is something that is in our hands.

And when it comes to something that is literally in my hands – my camera – I really don’t want to let go of the instrument that has brought me so much creativity and joy. I will also say that I sometimes feel disturbed when people say, “Oh your photographs are so nice – you must have a good camera”. I do, but there is so much more to this artform than just the device. Even as trends move away from it, I continue to learn and to grow within it.

So yes: the world, and not just the world of food blogging, is always changing – but we can have some constants, too. A decadent chocolate cake will almost without fail please anyone, for instance. In that sense, this is a timeless dish, and I hope you’ll enjoy my version of it.

Chocolate Cake

(Serves 5-6)

2 cups sugar

1¾ cups all-purpose flour

1 cup cocoa powder

1 teaspoon baking powder

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 teaspoon salt

2 eggs

1 cup buttermilk

1 cup hot water

1 tablespoon instant coffee

½ cup oil

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

Preheat oven to 170°. Prepare two 8’ cake tins by greasing, lining and dusting the pans.

Sift the flour, cocoa powder, baking soda, baking powder and salt – thus combining the dry ingredients. Add sugar.

Separately, add hot water to the coffee powder. Keep aside.

Using a hand blender, mix the eggs, vanilla extract, oil and buttermilk. You can make buttermilk at home by adding a tablespoon of white vinegar to a cup of room temperature milk, and allowing it to sit for 15 minutes before usage.

Add the dry ingredients to the wet ones and mix well.

Add the hot coffee to this mixture now. The batter will be a little runny. Avoid over beating.

Pour this batter into the two tins equally and bake for 30-35 minutes or until a skewer comes out clean. After the cakes sit for 15 minutes, turn them onto a tray and allow to cool completely. Decorate with chocolate icing.

If you’re new to all this and would like a little primer or refresher to the basics of baking, check out this citrus bundt recipe with lots of tips.

As I said earlier, this recipe is really the best one I know for the classic chocolate cake. I wonder how it will compare with ones you have made or tasted. I do hope you’ll enjoy it just as much as we do!